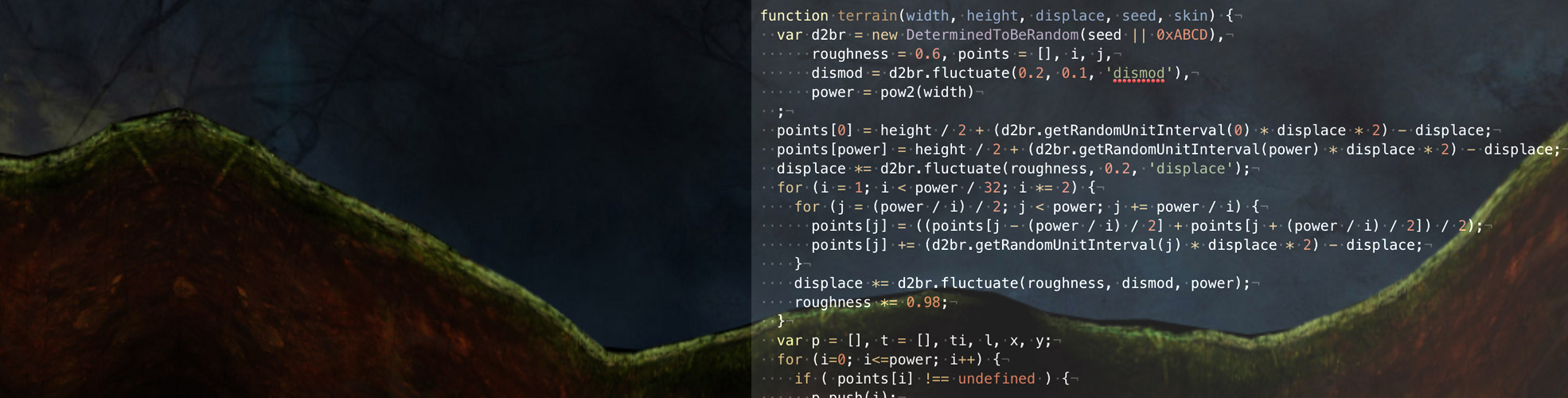

Seeded bidimensional skinable terrain generation

Thursday 5 May 2016

If you’ve been reading anything of my online ramblings over the last decade, then you’ll know I’ve been working (veeery slowly) on a certain labour-of-love called ALWTM. Most of the work involved has been to find the technologies that suit that of the project, and my unpredictable, non-linear, constantly-evaporating free time.

Here I’ll go into detail on my recent landscape generator (thanks in part to PixiJS’s mesh rope), which is helping to push forward my latest JS/HTML5/Canvas version.

Yay, polygons… again!

So first up, straight out-of-the-bag, in order to create something that looks, feels — and possibly bounces — like a 2D cross-section of a landscape, we’re going to need polygons. More specifically in this case, one big irregular multi-sided polygon. Thankfully, and for some odd reason, every single one of my personal projects has encountered the need for some form of polygon handling. So I have already done the research… in my opinion there is only one library to use when dealing with polygons, and that is the life-saving PolyK (thank you Ivan Kuckir!).

Now on to the second library you’ll want to use with Polygons. We’re going to need a system to help us draw them, otherwise we won’t be creating very tangible landscapes. This is not PolyK’s area of expertise, nor should it be. So my personal preference — for generating game-based graphics that are more on the visual side — is PixiJS. The main reason I feel that this library wins out above many others, is its ability to switch between WebGL and Canvas — and not to mention that Mat Groves (goodboy) is just awesome.

Neither PixiJS nor PolyK help with actually creating polygon co-ordinates however. Especially not predictably random polygon co-ordinates. The type of predictably random seeded co-ordinates that are a critical requirement — if you are going to magic up a solid-enough game object out of nowhere.

So, before those who have been paying attention go ahead and make the assumption that Polygons are actually the first step — we’re going to need a random generator. And not just any random generator… a well made, fast and predictable one.

Randomly predictable

The problem with random

If something is calling itself random, you usually want it to be truly random. The problem is most* computers can’t actually handle “real” random (whatever that is), they can only approximate it, and certain algorithms do better than others.

* I have no idea if the supposed quantum computers are imbued with the same seemingly unpredictability of the quantum world. If so, they might be able to handle random pretty well — including the possibility of the computer itself just unexpectedly popping out of existence.

However, in the normal — affordable and logical — computing world, most random functions you might use are simply applying predictable processes. The way they achieve apparent randomness, is by changing the initial input (the seed), and then hooking into an algorithm that generates a pattern of seemingly unconnected numbers onwards from that seed. So within this world — something that might cheer Descartes — it is possible that if you know all variables and processes involved you can predict the future, or recreate the past.

Because this fact normally detracts away from what random code is trying to achieve, most random functions hide away — or at least don’t expose — the ability that they can be reproducible. For example, take this excerpt from MDN’s Math.random page:

The Math.random() function returns a floating-point, pseudo-random number in the range [0, 1) that is, from 0 (inclusive) up to but not including 1 (exclusive), which you can then scale to your desired range. The implementation selects the initial seed to the random number generation algorithm; it cannot be chosen or reset by the user.

It is the last sentence this is the problem, at least if you need predictably random numbers. In fact many random generators are constantly changing their seed, usually based on the internal clock of the machine they are running on, so you have no way to predictably control the output.

Why a number generator?

The reason we want to control the output of our random function, is that it can be very useful in game development. Seeded number generators have been used across the years to cut down on things — that would otherwise be — expensive: in terms of data storage, processing, map design even NPC behaviour.

One of the most famous for employing a seeded number generator today will be Minecraft, but the game I first heard of using this technique (I’m sure there are much earlier examples) was Elite. The reason these games employ such a system, is that to attempt their game design in any other way would be impossible, because the time and space needed to design and store near infinite worlds is just that, impossible.

It also makes things more interesting for the developers, in that they don’t know everything about the world they’ve created — most recently highlighted in the advertising for No Mans Sky. The beauty I find in games that use number generators, is that on a basic level, you are essentially exploring a simple mathematical function — rather than a landscape, or the vastness of space. In a way it reminds me a little of the Barcode Battlers from when I was a kid.

ALWTM Implementation

I’m not planning to use the number generator to actually seed the game world, like the above. I’m just planning to use it to find pleasing auto-generated terrain out of the vast possible options. This is to help speed up my development, that has already taken far, far too long. I may implement some further uses of the number generator though, to help with random but partially predictable NPCs.

xxhash

So after deciding this would be my approach, I investigated what current implementations existed for JavaScript. This led me to this rather informative post on unity3d.com. A primer on repeatable random numbers takes you through what makes a good random generator, and introduced me to a very nice visual technique for checking the output — using co-ordinate plotting.

It also introduced me to xxhash, which did exactly what I needed. Gave me a nicely random number generator, that I could predictably control via an initial seed value. This allowed me to produce the landscape generator seen below — reminiscent of the original Worms game.

Also similar to that game, with this generator I can:

-

Change the “theme” used, and even introduce landscape distortion — thanks to PixiJS’s mesh Rope, which is used to apply normal PNG graphics along a polygon shape.

-

Destroy the surface — thanks to the Polygon clipper.js library, that allows boolean operations on polygons (Thank you Timo and Angus Johnson).

-

Collision detect along or inside the surface, thanks to Polyk and its raycast ability.

And there is no data storage to talk about, the only things I need to store are:

- The “theme” graphics as a PNG file

- The code involved as JS files

- The initial seed, which for the first 4 tabs below is “bumpy”

Each time the landscape is generated from that seed, it will be the same. So far, in all my tests the JS implementation of xxhash has worked well across different devices. This is something to be aware of in terms of number generators and hashes. Depending on the underlying boolean/number architecture used, it can cause the results to different across devices. Especially if the algorithm uses bit shifting or rotation. I have yet to find an issue with xxhash though.